Each week, David Souter comments on an important issue for APC members and others concerned about the Information Society. This week’s blog is about the growing role of intermediaries in information access.

Each week, David Souter comments on an important issue for APC members and others concerned about the Information Society. This week’s blog is about the growing role of intermediaries in information access.

The Internet, we all agree, has transformed access to information. Those of us with broadband access – though, let’s remember, that’s a minority worldwide – can, increasingly, access any information, from anywhere, at any time, and use that information in whatever way we like.

More access to more information, from more sources, we all agree, is beneficial. More information should enrich our lives, enable us to make better decisions, enhance our social networks, give us more economic opportunities, help us to live long and prosper.

But, as ever, let’s be cautious, let’s ask questions.

Changing information access

The Internet’s not the first step change in information access like this: maybe the fourth. The invention of writing thousands of years ago, of printing around the middle of the last millennium, of broadcasting in the last century: all of these greatly expanded the reach of information and the range of it to which we could gain access, as the Internet is doing now.

Two differences, however. The pace at which the Internet’s become available is far faster than the spread of writing, printing or broadcasting. And the scale of growth in information that’s available is far, far greater. Those of us with sufficient bandwidth can get access to much of that; those without to much much less.

A couple of weeks ago, I wrote about the implications of this for equality: that unequal access to a growing range of information can reinforce the gap between those that have wealth and power and those that don’t. Today I’m going to raise a different challenge: How do we handle too much information? Who helps us do so? And what impact might they have on our futures?

The growth of information

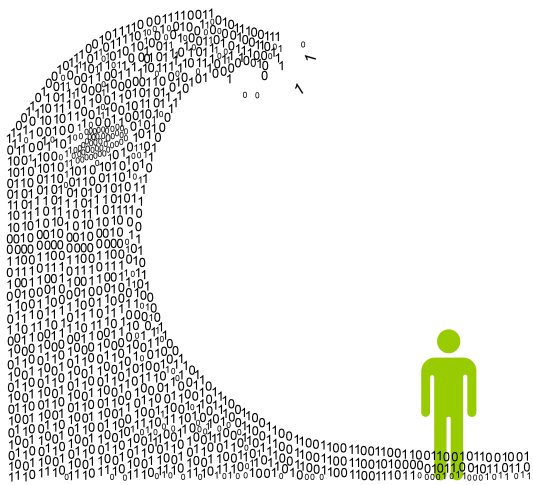

The basic issue’s pretty clear. The information that’s available to us is increasing (almost) exponentially (and, for once, that word is not hyperbole). There’s far more information out there, about everything, than we could ever possibly use, but very few of us have the time or the range of skills required to navigate it, even where we’ve expertise. We have better data storage, but the same old brains. We’re content-rich but increasingly time-poor.

The volume of content may be growing exponentially, therefore, but our personal capacity to process it remains the same. We need help to do so, and who helps us matters.

The danger of the echo chamber

There are two issues that arise from this. Quite a lot’s been written about one of these. More information and more ways to share it (particularly social media) are not leading us to explore a wider range of information or ideas, it’s suggested. Instead, they’re leading us to spend our time with the kind of content we already like, and with the viewpoints we already share.

More information, in other words, is not extending our cultural experience or exposing us to new ideas. Instead it’s encouraging us to stay in echo-chambers, listening to those who agree with us, and experiencing more of what’s familiar. Some suggest that this is polarising our societies, not bringing them together.

The business model of the Internet

The advertising business model that underpins free Internet services drives this phenomenon because we’re likeliest to spend our money on more of what we know than to experiment with unfamiliar things. We’re nudged to buy books and music that past purchases suggest we’ll like, towards social media contacts who might share our views or our experiences, towards news items that our browsing history suggests will be of interest, to political commentators whose views we’re likeliest to share.

Of course, we gain value from being directed towards things we might enjoy or people we might like. But that value isn’t ours alone. Concentrating our minds on the familiar adds value to advertisers and intermediaries too.

The role of intermediaries

Which brings me to my second issue. As individuals, with limited intellectual capacity and time, we’ve always used information intermediaries to point us to the information we need and find the entertainment we’ll enjoy. Librarians have been obvious intermediaries. But so have friends and relatives, publishers, newspaper proprietors, broadcasters, teachers, priests. Everyone has their own favourite sources of advice and guidance.

The exponential growth in data we’re now experiencing has changed our choice of information intermediaries and the way we use them. In place of those familiar humans, or at least alongside them, we now use online service providers. We use Google to search the Web; we respond to messages that Facebook highlights; we browse the hints YouTube and Amazon present us with; we compare the market for insurance policies on price comparison sites, we trust the wisdom of Wikipedia.

We rely on the algorithms these services create. And in doing so we’ve ceded much of our new information age autonomy to third parties who have their own interest in how we use the information they provide.

What’s more, because the quality of service provided by online services like search engines depends on the number of people that use their algorithms, there’s a tendency towards monopoly in interactive information gateways. We can see this in the dominant positions which have been established by leading services like Google, Facebook, Twitter, Amazon, Wikipedia, YouTube (and their equivalents in China).

So what to do?

Let’s return to the assumptions with which I began. We have more access to more information from more sources than before, and that access is growing day by day. Good. But, for that access to be useful, we rely on intermediaries. We’ve not acknowledged this sufficiently, or thought enough about its implications. What should we do?

First, we should recognise that superabundant information is a mixed blessing. It’s only useful if we have the tools to make effective use of it. We don’t ourselves, which is why we rely on intermediaries. But our capacity can be improved. What can be done to develop users’ skills to find the information that they want, to validate content, to interrogate its source, its purpose, its potential value, its potential harm?

Second, we should understand the power that information abundance gives to intermediaries and to the algorithms that they develop and deploy. In an age when meaningful access to abundant information depends on intermediaries, it’s better if people have access to a range of intermediaries, which use different ways of assessing what we want, need or use. Are there ways in which policymakers can encourage that diversity?

Third, we should consider the ethics of information intermediation. So far the Internet community has focused on issues like net neutrality, which seeks to ensure that intermediaries make all content available. But people don’t want access to all content when they use intermediaries; they want to be pointed towards the content that’s most useful to them, and away from what is not. What happens if intermediaries start to use those algorithms to influence their social or political as well as their commercial choices?

Intermediaries are essential for effective information access in the Information Society. They are just as important in determining what that Information Society will look like as the underlying technologies that drive the Internet. We should try to ensure they take us where we want to go, not just where they want us to go.

‘Inside the Information Society’ will be taking its Northern-midsummer/Southern-midwinter break over the next two weeks, but will be back on the 30th of August with a look at what ICTs are doing to jobs.

Image by Mark Smiciklas used under Creative Commons license.

David Souter is a longstanding associate of

David Souter is a longstanding associate of