A lot is written these days about the internet’s effect on childhood: what it can do to improve learning and enable children’s voices to be heard, not least during the COVID-19 crisis; the ways that it may threaten children’s safety or increase inequality of opportunity. I added to this on this blog quite recently.

This week, one aspect of that: the way that children’s experience of culture’s changed over the generations, with some questions about what that means. And some nostalgia.

A caveat

I’m conscious that this experience is culture-specific. There’s a novel about lost childhood innocence called The Go-Between that was once popular in Britain (also a film). It’s remembered today mostly for its opening line: ‘The past is a foreign country; they do things differently there.’

That’s true and so is its obverse: that different countries have different pasts. So I’ll draw here on my experience, within my country, but aim to draw out threads that have a wider resonance.

My core question’s this: how have the different communications ‘opportunities’ available to successive generations of children affected their experience of culture? Four generations; four different experiences.

My parents’ generation

My parents were born just before the First World War, in poverty, in northern England. Almost no-one in their time in their communities, while growing up, had telephones. Television lay in the distant future. They experienced the dawn of broadcast radio (my teenage father built the family’s first sets) and the early days of cinema (silent, black and white, usually American and comic).

Their cultural environment was based round family and friendship groups, playing in the streets, the shared assumptions and experiences of the (coal-mining) community in which they lived rather than the wider national community. Communal rather than analogue, perhaps, and a long, long way pre-digital.

My generation

I was born in the mid-1950s and grew up in a different communications world, much more linked to national and global culture. I knew the radio from infancy, and we had a television (tiny, black and white) once I was five; the telephone at home (shared with a neighbour family) when ten. But still nothing, of course, remotely like the internet.

My early media memories are of broadcasting aimed at the child: radio and TV programmes for the very young (Listen with Mother; Watch with Mother – this was a very patriarchal time); radio programmes made for schools to use as lessons; an hour of children’s TV after school (cartoons and nature programmes featured heavily). Books, many written with assumptions about richer children’s lives. Occasionally, a Disney cartoon film.

This was a richer screen culture than my parents’ but was still quite narrow. More importantly, for my argument today, it was heavily curated by what we’d now call content providers, especially national broadcasters, with powerful assumptions about what was good and what appropriate for children.

My children’s generation

My children were born thirty years ago, just before Tim Berners-Lee devised the World Wide Web, and by that time the ethos of children’s entertainment had moved on a lot.

Books for kids were much more democratic, much more about the lived experience of the majority. Radio was fading, but children’s TV was a lot more varied and sophisticated: in colour, but also much more colourful in content and much more rooted, too, in children’s lived experience (the first and most famous British real-life school-based soap-opera, Grange Hill, began in 1978).

There were many films for children, not just Disney films. Video games were popular, including games for smaller children, but they played on the first PCs and look astonishingly basic compared to games on even basic phones today.

Some of this childhood generation had televisions in their rooms, but TV channels were still few: there was nothing like the diversity available today. Some began to have their own mobiles, in my kids’ case from when they went to secondary school at age eleven, but those mobiles were only phones, not entertainment consoles. The Web was still quite basic, without video streaming. There was no YouTube, no Facebook, no Instagram.

It was parents who mostly curated these children's experience of media and culture, which was still largely shared within the family, not least as families clustered round the television. Private access to online content through personal devices still lay in the future.

And today

But today that private access to a vast array of content from a vast array of sources, using personal devices, has become the norm. My grand-daughter’s too young as yet (at six months), and her early experience will still be curated for her (yes, I’m looking forward to sharing those VHS videos that I still have from her mother’s childhood), but she’ll be making her own choices about what to watch and how much sooner than her parents could.

The British regulator Ofcom’s just published its latest evidence on children’s online cultural experience, and it illustrates the change over a generation.

-

Almost every child in Britain today has internet access at home (though about a fifth don’t have appropriate devices for schoolwork, which has been important during COVID).

-

Tablets are the commonest intro hardware to the digital for pre-school and early primary-age children.

-

Those aged between seven and sixteen spend nearly four hours a day online (a generation ago, that level of TV engagement would have caused concern).

-

YouTube is the favourite app for almost all within those age groups and its use is almost universal (only teenage girls disclosed a different top app, Tik Tok).

-

Three-quarters of five to fifteen year olds play games online.

-

Just under 60% of British children are on social media platforms by the time they are eleven – 95% by the time they are fifteen – though most platforms set their minimum age at thirteen.

Changing curation

One thing that’s obviously changed here, over the generations, is curation. The content that I saw as a child was largely chosen for me by a small range of content providers, with government regulation and parental supervision. My children’s generation’s experience was substantially curated, too, by parents.

Today, children’s entertainment options are primarily derived online. They’re curated by themselves – or, perhaps I should say, by themselves within a framework determined by peer pressure and by the algorithms deployed by companies that benefit from the choices that they make. And they’re made up substantially of material that’s being made by individuals – their friends, those they admire, self-styled ‘influencers’, and sometimes those who’re seeking to exploit them – as much as by traditional content providers.

What are the implications?

This is substantially different from the ways that previous generations entered into the wider cultural environment – not just entertainment, but also social engagement – of the world in which they’re growing up.

Some implications of this shift from intermediated to more personal curation are discussed quite widely.

Ofcom’s research found that most twelve to fifteen year olds reported negative experiences online, including unwanted contacts, violence, disturbing sexual content and bullying. Risks from sexual predation and the pornification of adolescent sexual awareness are increasingly discussed in public policy on online regulation. More attention’s also being paid to risks from bullying and harassment and to commercial exploitation of children through advertising, online gambling, in-app purchases.

Implications such as these are relatively easy to identify, as are changes in consumption patterns for aspects of youth culture – such as how music is consumed, or information accessed on subjects of especial interest. More research on these, though, would be useful, particularly in contexts where different groups of children have different experiences – because of class or gender, for instance, or specific vulnerabilities, or because of different cultural attitudes within their families, communities and cultures.

Long-term implications

But there are long-term changes also worth consideration. What impact, for instance, is more independent access to entertainment choices and cultural engagement having on relationships between children and adults? In my teens, families clustered round their one TV; today, that’s much less common, cultural experience is much more individual. What impact does that have on the community of interest and shared understanding of what’s happening within the family? Likewise between siblings and in friendship groups, especially round adolescence?

What’s the relationship between individual curation – each person’s or each child’s experience of the apps they use, the content they explore (and don’t explore) – and the platforms that offer content? How much curation’s really individual and how much led by algorithms that seek to maximise ad revenue or point users towards content that will do so?

What’s the relationship between content curation and creation, when it’s easy for anyone to make their own content but harder to gain traction for it in an algorithm-led environment?

And what differences are there to be found between different cultures and different countries in this context? Differences arising from different cultural heritage and norms; different patterns of family and domestic life (including possibilities of privacy); different degrees of engagement with the online world (digital inequalities); different degrees of censorship and management of the online environment; the different extent to which digital experience is framed by local or by global content (and the influence therein of global platforms based in the United States and China)?

These questions aren’t concerned solely with children, obviously, but the experience that we have as children shapes our later lives. That makes understanding the changing nature of children’s experience important for future public policy – not just their experience of the benefits of online services or the risks of online harms while they are children, but the experience that they have of culture, cultural and social integration generally that will to a significant degree make them the adults they become.

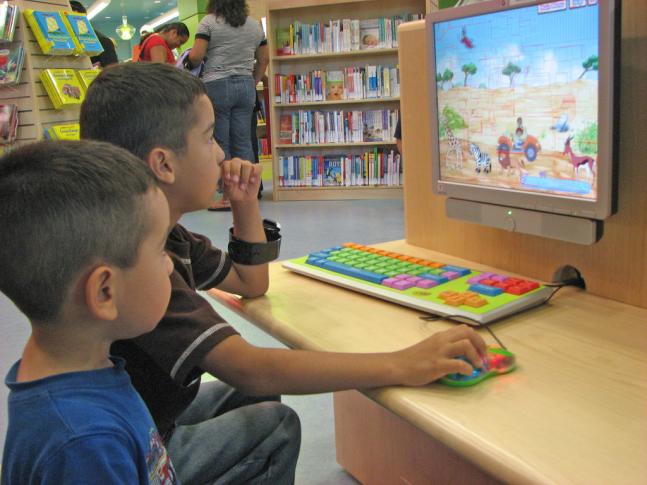

Image: Children using computer, on Wikimedia Commons.