In October 2015, the UN Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression David Kaye will present a new report on the protection of sources and whistleblowers before the United Nations General Assembly in New York. APC welcomes these efforts to strengthen protections that enable accountability and transparency on a national and global level, which is why we contributed this submission to Mr. Kaye’s consultation.

Whistleblowers reveal misconduct, human rights violations, corruption and other abuses at great personal and professional risk. They are routinely subject to harassment, job termination, arrest, and even physical attacks for exposing wrongdoing. Whistleblowers need strong legal protections to protect them from retaliation and enable them to report offences safely and freely.

As the world’s longest-running progressive network of civil society organisations working with information and communications technologies (ICTs) for social justice and sustainable development, celebrating its 25th anniversary this year, APC has been troubled by trends over the last decade which show that internet rights are increasingly violated and believes that the attempts to censor leak platforms provide additional reasons for concern. Even in contexts where there are laws in place to protect whistleblowers, these laws are rarely enforced or are completely ignored. The courageous actions of whistleblowers defend human rights, save lives and billions of dollars in public funds, and contribute to making governments more transparent and companies more accountable.

We specifically urge Mr. Kaye to include in his report that:

-

Whistleblowing is an integral part of freedom of expression, protected under Article 19 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) as well as other standards such as the UN Convention against Corruption.

-

The implementation of Article 33 of UN Convention against Corruption in domestic legal systems is crucial for the protection of whistleblowers and for their contributions to be taken seriously.

-

While nearly a third of UN member states already have laws covering whistleblower activity, some legal frameworks, such as those in the United States and United Kingdom, have proved seriously inadequate when the information disclosed concerns the activities of the state itself, especially when national security is invoked.

-

Whistleblowers in the USA face disproportionately severe penalties for the disclosure of classified information, pursuant to the Espionage Act of 1917.

-

With the proliferation of electronic surveillance over the previous decade, the safety of anonymous sources and whistleblowers no longer depends only on ethical and legal protections, but also on information security.

-

The majority of journalists and civil society organisations still exchange confidential information over regular phone lines, text messages and unencrypted email. This is a significant challenge, especially within the context of state or corporate surveillance, as the relevant actors can sidestep the legal protection of sources and whistleblowers, and identify their identities by other means.

-

NGO activists, academic commentators, and other professions that rely on being middle-people to carry information of public interest to the public deserve the same right to protection of sources as journalists, to ensure that sources are not deterred from conveying important information to them.

-

It is crucial to update regulation that protects the confidentiality of journalists’ sources to include digital aspects

-

The gaps in protection for whistleblowers and secure online communication tools have led to the rise of internet leak platforms that enable anonymous whistleblowers to deliver information without placing themselves at great risk. These platforms enable and support whistleblowing and investigative journalism.

-

These types of secure platforms have sometimes failed however, to prevent significant reprisals against people who have leaked documents to them. We note the cases of US army private Chelsea Manning, activist Jeremy Hammond, and writer Barrett Brown who have been all sentenced to prison.

-

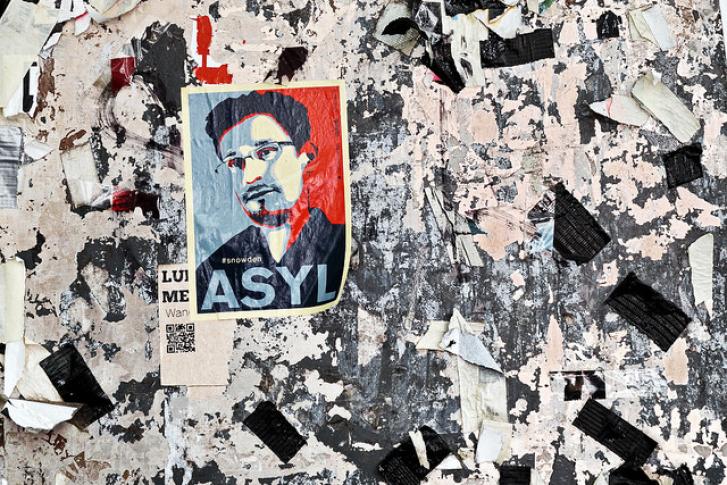

These leak platforms and other related internet platforms have also been subject to attacks. Companies have been pressured to surrender private data and to stop providing services to such platforms and people associated with them. In one case, email service provider Lavabit was forced to close down in 2013 after it was asked by the US government to compromise its entire privacy system for the sake of eavesdropping on a single customer, largely presumed to be Edward Snowden, a whistleblower who revealed mass surveillance and misconduct by the US National Security Agency.

-

The internet has to offer potential whistleblowers the power to decide where and when to disclose information. Whistleblowers can choose to disclose information in countries other than their own to take advantage of a stronger protection of sources.

-

Whistleblowing does not work in countries where there is no rule of law.

Furthermore we make the following recommendations:

-

Given the recent examples of serious retaliation against whistleblowers, we believe that their international protection must be strengthened and that it is time for the international community to consider concrete steps to bridge this protection gap.

-

States and international bodies regulating the protection of sources should allow the practice of that right to be applied to a wider definition than traditional journalists. Furthermore, they should ensure that protection of sources and whistleblowers goes beyond corruption and extends to those who reveal human rights violations.

-

States should not attempt to silence critical voices and information pertaining to the public interest – particularly those hosted in jurisdictions outside their own.

-

States and the internet community should explicitly reject any form of online content control that limits freedom of expression and information, particularly information that contributes to more transparent governance, empowers citizens to hold their governments accountable, and reveals violations of human rights.

-

States should respect the right to privacy online and not seek to circumvent the protection of sources and whistleblowers’ anonymity by monitoring electronic communication or requesting private information from intermediaries.

-

States should accede to and ratify the UN Convention against Corruption, and seek to implement Article 33 of said convention into their domestic legal systems.

-

Online whistleblowing technologies such as leak platforms and other forms of secure, anonymous online communications tools remove many of the technological barriers to ensuring the safety of sources and whistleblowers. As such, states and international bodies have a duty to protect such technologies and to promote them.

-

Journalistic institutions, civil society and other organisations dealing with confidential sources need to institute capacity-building programmes for their staff regarding secure online communications and establish secure protocols for sourcing privileged information.

-

Civil society, citizen journalists, and platforms that handle privileged information revealing misconduct or abuses need to use the same code of conduct established by journalistic institutions and pay attention to the privacy implications of information that they release.