By Ysabel Briceño and AL Publisher: APCNews MERIDA,

Published onPage last updated on

In the last few years, a technical problem related to internet traffic and the broadband market emerged and was recognised as hindering the quality of communications in South American countries: the long distance that most internet traffic had to travel outside of the region and then back again, even in the case of local communications.

Gráfico del crecimiento de internetInternet backbones – the main “trunk” connections that link the different ramified networks of internet traffic in Latin America – and global internet service providers are primarily located in the United States. This meant that initially, all local, national and international data circulating on the internet in the Latin American countries inevitably had to pass through these backbones before returning to their final destination in the region. This situation entailed longer delays in data recovery, the loss of data packets and, of course, higher costs for internet end-users, since the services of international service providers had to be purchased for all internet traffic. This posed a significant obstacle to the growth of the sector in Latin America.

Gráfico del crecimiento de internetInternet backbones – the main “trunk” connections that link the different ramified networks of internet traffic in Latin America – and global internet service providers are primarily located in the United States. This meant that initially, all local, national and international data circulating on the internet in the Latin American countries inevitably had to pass through these backbones before returning to their final destination in the region. This situation entailed longer delays in data recovery, the loss of data packets and, of course, higher costs for internet end-users, since the services of international service providers had to be purchased for all internet traffic. This posed a significant obstacle to the growth of the sector in Latin America.

The creation of network access points (NAPs), also know as Internet Exchange Point (IXPs), was identified as a means of remedying this problem. By facilitating the exchange of internet data traffic within a particular geographic area (a country or region), it would be possible to avoid channelling traffic through international routes when there was no need for it to leave the area.

It is generally assumed that the creation of national and regional NAPs will not only improve the quality of internet access in the countries of Latin America, in terms of connection speed and reliability, but will also contribute to lowering the costs of service by eliminating expenditures on international service providers

Venezuela is one of the few countries in the region that has not succeeded in implementing plans for the creation of a NAP. The academic, private and state sectors have all promoted the creation of shared points of internet connection, for reasons that have varied over time: from scientific necessity to economic benefit to technological independence and sovereignty. And all have proven unsuccessful.

More recently, the new initiative for the creation of a NAP promoted by the state is tainted by the politically polarised climate currently gripping Venezuela. Mistrust, conflicting priorities, power relations and fear of excessive control by the state have thrown up new obstacles to negotiations for the creation of a NAP. In a country where political agreements are a major challenge, it is difficult to say what the possibilities of success will be for this latest proposal from the state.

At the same time, however, the unsuccessful efforts to create a NAP in Venezuela over the course of an entire decade raise the question of whether new technological developments might not offer solutions for the initial goals to be fulfilled through a NAP: greater efficiency and lower prices for end-users. Thanks to the emergence of new technologies, the convergence of services and decreases in international connectivity prices, it is quite likely that at this point in time the creation of a NAP is losing the relevance it had in earlier years.

The resurgence of the idea of a NAP in Venezuela, promoted by the government and based on a strategic conception of the sector, has complicated negotiations by lending the initiative new connotations. A new relationship between the state and the telecommunications sector is developing, one that is not only economic but also political. Over the last decade, the internet has become a powerful tool and its capacity to influence diverse sectors of society has made it a major force in this new century. Along the way, both the state and society, in their complex interrelationship, are putting their cards on the table, making offers, exerting pressure, in accordance with the difficult expectations developed in this 21st century. New contexts, new forms of negotiation.

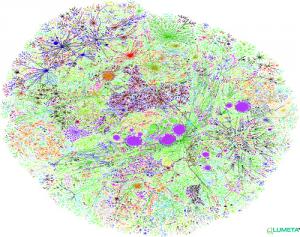

Photo: Organic growth of the internet and its sub-networks, by jurvetson. Used with permission under Creative Commons licence 2.0

This article is based on a report by Ysabel Briceño as a part of the CILAC initiative, a project by APC’s Policy Programme for Latin America. This report is part of a “series of five reports on ICT reform and access to broadband in Latin America”:http://www.apc.org/en/node/8974